Tubes having very small diameters (narrow cylindrical tubes) are called capillary tubes. If these narrow tubes are dipped in a liquid, it is observed that the liquid in the capillary either rises or falls relative to the surrounding liquid level. This phenomenon is called capillary action, and such tubes are called capillary tubes.

A wet fluid displays the type of capillary action that is further caused due to the forces of cohesion and surface tension acting together. Capillary action is the resultant of intermolecular attraction between the molecules of water and the adhesive force in between the walls of the capillary and the liquid.

Table of Contents

- What Is Capillary Action?

- Application of Newton’s Second Law

- Important Points Regarding Capillarity Action

- Relationship between Excess Pressure and Surface Tension

- Difference between Concave, Convex and Plane Meniscus

- Applications of Capillarity

- Forces in Capillary Action

What Is Capillary Action?

We can define capillary action as a phenomenon where the ascension of liquids through a tube or cylinder takes place. This primarily occurs due to adhesive and cohesive forces.

The liquid is drawn upward due to this interaction between the phenomena. The narrower the tube, the higher will the liquid rise. If any of the two phenomena, i.e., that of surface tension and a ratio between cohesion to adhesion, increase, the rise will also increase. Although, if the density of the liquid increases, the rise of the liquid in the capillary will lessen.

The amount of water that is held in the capillary also determines the force with which it will rise. The material that surrounds the pores fills the pores and also forms a film over them. The solid materials that are nearest to the molecules of water have the greatest adhesion property. The thickness of the film increases as water is added to the pore, and the magnitude of capillary force gets reduced.

The film that was formed on the outer surface of the soil molecules also may begin to flow. The capillary action is what causes the movement of groundwater through the different zones of soil. How the fluids are transported inside the xylem vessels of plants is also by the capillary action. As the water evaporates from the surface of the leaves, water from the lower levels, that is, the roots, is drawn up by this phenomenon.

In essence, liquids have the property of being drawn into minute openings, such as in between the granules of sand and rising into thin tubes. Solid substances and liquids have an intermolecular force of attraction in between them, and due to the result of that, capillarity or capillary action takes place. The same thing happens when a sheet of paper is placed on a puddle of water, i.e., absorbs it. This happens because the water gets absorbed into the thin openings between the fibres of the paper.

Application of Newton’s Second Law

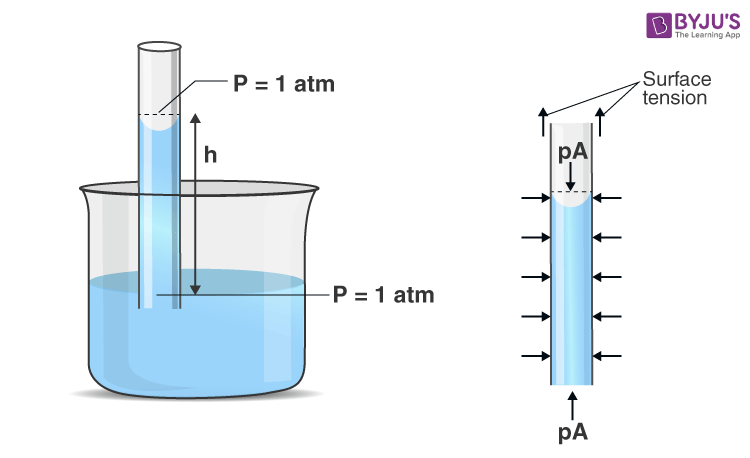

We will explain the phenomenon by applying Newton’s second law to the liquid column. To apply Newton’s second law, the free body is chosen (as shown in Figure 1) so that we can define net force on the liquid column contact forces are those exerted by the liquid surrounding the column; these adhesive forces do not act on this body and therefore will not be counted.

Also Read: Newton’s Laws of Motion

The pressure at the top and bottom of the column is 1 atm, and so these forces balance each other. Similarly, horizontal pressure forces along the sides of the liquid column balance each other. So, the remaining vertical forces must balance. In the vertical direction weight of the liquid column (mg) acts downward, and the force of surface tension acts in the upward direction, which acts along a circle of radius r.

According to Newton’s second law,

Force by surface tension – mg = 0

TL – mg = 0

Where,

mg – the weight of the liquid

TL – is the surface tension force

This is the desired result of the rise of liquid in the capillary tube.

Another way we can derive the capillary rise is through excess pressure in order to find the height to which a liquid will rise in a capillary of radius R dipped in a liquid. It is shown in the figure. The meniscus is concave and nearly spherical. As we know, the pressure below the concave meniscus will be less than the pressure above the meniscus by

Where,

P0 – is atmospheric pressure

r – is the radius of the meniscus

T – is surface tension

Since,

The liquid will flow from higher to lower pressure, and at the same level, liquid pressure must be the same, so the liquid will rise in the capillary till the hydrostatic pressure of the liquid compensates for the decrease in pressure.

From Figure (2), it is found that the relationship between the radius of the meniscus (r) and the radius of the capillary (R) will be,

Substitute Equation (3) by Equation (2)

Important Points Regarding Capillarity Action

(i) Capillarity Depends on the Nature of the Liquid and Solid

i.e., T, P, R and Q

Where,

T – surface tension

ρ – density of liquid

R – radius of the capillary

Q – the angle of contact

If θ > 90°:

The meniscus is convex, and h will be negative (h = -ve), which means the liquid will fall (descend) in the capillary.

i.e., actually, it happens in the case of mercury in a glass tube.

If θ = 90°:

This means the meniscus is plane, so (h = 0), and there is no capillarity.

If θ < 90°:

The meniscus is concave, and h will be positive (h = +ve). This means the liquid level rises up (ascends) in the capillary, which is shown in Figure (3).

(ii) Angle of Contact

The angle of contact is defined as the angle between the tangent drawn to the liquid surface at a point of contact of the liquid and the solid inside the liquid. It depends on the nature of both solid and liquid. For concave, the meniscus of liquid will be acute, and for convex, the meniscus of liquid will be obtuse.

(iii) For a Given Liquid and Solid at a Given Condition, P, T, Θ and G Are Constant

Hr = constant ……………….(5)

i.e., the lesser the radius of capillarity (R) and greater will be the rise and vice-versa.

(iv) Independent of the Shape of the Capillary

At equilibrium, the height (h) is independent of the shape of the capillary (If the radius of the meniscus remains the same). This is why the vertical height (h) of a liquid column in capillaries of different sizes and shapes will be the same. (If the radius of the meniscus remains the same and then the vertical height (h) of the capillaries also remains the same even for different capillaries). It is given below in Figure (4).

In capillarity, the excess pressure is balanced by hydrostatic pressure and not by force due to surface tension by weight.

In general,

And

TL = mg

Equation (2) is valid only for cylindrical tubes and cannot be applied to other situations shown in Figure (4). But Equation (1) is the general case (v). In case of a capillary of insufficient length (L < h) (the capillary is less than the excepted rise of liquid), the liquid will neither overflow from the upper end, i.e., fountain, nor will it tickle along the vertical sides of the capillary. The liquid, after reaching the upper end, will increase the radius of its meniscus without changing its nature in such cases.

Liquid Meniscus in Capillarity

In capillarity, the liquid meniscus can be:

(i) concave meniscus

(ii) convex meniscus

(iii) plane meniscus

To understand this, let us take a liquid drop (or) bubble; as we know, due to the property of surface tension, every liquid tries to minimise or contract its free surface area. Similarly, a liquid drop or bubble also tries to compress (contract) its surface, and so it compresses the matter enclosed.

Also, Read: Fluid Dynamics

This, in turn, increases the internal pressure of the liquid drop or bubble, which prevents further contraction, and equilibrium is achieved. In the equilibrium state, the pressure inside the bubble or drop is greater than outside the bubble or liquid drop, and this difference in pressure between inside and outside the liquid drop or bubble is called excess pressure.

In the case of a liquid drop

For a liquid drop, excess pressure is provided by the hydrostatic pressure of the liquid.

In the case of a bubble

For the bubble, the excess pressure is provided by the gauge pressure of the gas confined in the bubble.

Relationship between Excess Pressure and Surface Tension

To derive the relationship between surface tension and excess pressure for a liquid drop (or bubble inside the liquid), let us consider a liquid drop of the radius (r) having internal pressure and external pressure Pi and Po, respectively.

So, it excess pressure P = Pi – Po. If we want to change the radius of the drop from r to r + dr, then we have to do external work.

External work (W) is done = F. dr = P A dr ………….(1)

Because,

While changing the radius of the drop from r to r + dr, the change in area will be changed in the area,

The work done in changing the area will be very much similar to the work done in stretching a rubber sheet. So, this work will be stored as potential energy on the surface, and the amount of this energy per unit area of the surface under isothermal condition is called “intrinsic surface energy (or) free surface energy density.”

W = T dA ……………(4)

Where

W – work done in changing the area

dA – change in the area

T – surface tension

Equation (2) is called surface energy.

According to surface energy,

Equation (7) is called excess pressure.

Where P is the excess pressure.

For Bubble in Air:

Similarly, for a bubble in the air: As we know, bubbles in the air will have two surfaces. The pressure inside the bubble is Pi, the pressure outside the bubble is Po, and the pressure between the two surfaces is P.

So, excess pressure will be

From equations (6) and (7), it is clear that excess pressure will be inversely proportional to the radius, which means a smaller radius will have more pressure and vice-versa. This is why when two bubbles of different radii are put in communication with each other, the air will rush from smaller radii to larger radii bubbles, due to which smaller bubbles will shrink while larger bubbles will expand till the smaller bubble reduces to a droplet.

Excess Pressure-flow Direction

Excess pressure in case of liquid drop or bubble in liquid is directed from inside to outside (inner will have more pressure than outer) [From concave to convex side]. This result is true for the meniscus of liquids.

(i) Concave Meniscus

For concave meniscus, pressure below the meniscus will be less than the pressure above the meniscus by

Where

r – is the radius of the meniscus.

(ii) For Convex Meniscus

For a convex meniscus, pressure below the meniscus will be higher than the pressure below the meniscus. Pressure above the meniscus will be Po, and pressure below the meniscus will be

Where, r – radius of the meniscus.

(iii) Plane Meniscus

For a plane meniscus, the pressure difference between above and below the meniscus will be zero (excess pressure = 0), so there is no capillarity.

Difference between Concave, Convex and Plane Meniscus

| Concave Meniscus | Convex Meniscus | Plane Meniscus |

| Pressure below the meniscus \(\begin{array}{l}\left( {{P}_{o}}-\frac{2T}{r} \right)\end{array} \) is less than pressure above the meniscus (Po) |

Pressure below the meniscus will be \(\begin{array}{l}\left( {{P}_{o}}+\frac{2T}{r} \right)\end{array} \) higher than pressure above the meniscus (Po) |

Pressure below the meniscus = Pressure above the meniscus |

| Excess pressure will be \(\begin{array}{l}P={{P}_{\text{above}}}-{{P}_{\text{below}}}\end{array} \)

\(\begin{array}{l}P=\frac{2T}{r}\end{array} \) |

Excess pressure (P) \(\begin{array}{l}P={{P}_{\text{below}}}-{{P}_{\text{above}}}\end{array} \)

\(\begin{array}{l}P=\frac{2T}{r}\end{array} \) |

Excess pressure (P) = 0 |

| The angle of contact is acute (θ < 90°) | The angle of contact is obtuse (θ > 90°) | The angle of contact is θ = 90° |

| The liquid level in the capillary ascends | The liquid level in the capillary descents | No capillarity |

| The liquid will wet the solid | The liquid will not wet the solid | Critical |

Applications of Capillarity

(a) The oil in the wick of a lamp rises due to the capillary action of threads in the wick.

(b) The action of a towel in soaking up moisture from the body is due to the capillary action of cotton in the towel.

(c) Water is retained in a piece of sponge on account of capillarity.

(d) A blotting paper soaks ink by the capillary action of the pores in the blotting paper.

(e) The root hair of plants draw water from the soil through capillary action.

Forces in Capillary Action

Cohesion

The force that exists between the molecules of specific liquids is termed cohesion. Raindrops, before they fall to the earth, are also kept together by the same force. Surface tension is a phenomenon that most of us are aware of, but not many of us know that it is also due to the concept of cohesion. Surface tension allows objects that are denser than the liquids to float on top of them without any support and doesn’t let them sink.

Check out: Difference between Adhesion and Cohesion

Adhesion

Another concept that can be understood with this phenomenon is one of adhesion. Adhesion is the force of attraction between two dissimilar substances, such as a solid container and a liquid. This is the same force that allows water to stick to the glass.

If the phenomenon of adhesion is more than that of cohesion, the liquids wet the surface of the solid it is contacted with, and one can also notice the liquid curving upwards towards the rim of the container. Liquids like mercury have more cohesion force than adhesion force, and thus can be termed non-wetting liquids. Such liquids curve inwards when near the rim of the container.

Capillary Action in Everyday Life

-

If you drop a paper towel in water, you’ll see it climb up the towel spontaneously, apparently ignoring gravity. In reality, you see capillary movement, and it is about right that the water molecules crawl up the towel and pull on other water molecules.

-

Without capillary action, plants and trees will not be able to survive. Plants hold roots in the soil that can bring water from the soil up into the plant.

-

Nutrients dissolved in the water get into the roots and starts to climb up the surface of the plant. Capillary activity helps deliver water to the roots.

Frequently Asked Questions on Capillary Action

Give a reason why the sponge absorbs water against gravity.

When we take a sponge and place it in a shallow plate of water where the water level is lower than the sponge’s height, the sponge collects water until it is wet, including a part of the sponge that is above the water level, due to the capillary action.

What are the factors responsible for capillary action?

The adhesive, cohesive forces and surface tension are responsible for capillary action. The friction at the surface serves to keep the surface intact. Capillary action happens when the adhesion between the liquid molecules becomes greater than the cohesive forces.

Give examples of capillary action.

Water moving up in a straw or glass tube against gravity, tears moving through tear ducts, water moving through a cloth towel against gravity, etc., are examples of capillary action.

Comments