Introduction to Units and Dimensions

Every measurement has two parts. The first is a number (n), and the next is a unit (u). Q = nu. For example, the length of an object = 40 cm. The number expressing the magnitude of a physical quantity is inversely proportional to the unit selected.

Download Complete Chapter Notes of Units and Measurements

Download Now

If n1 and n2 are the numerical values of a physical quantity corresponding to the units u1 and u2, then n1u1 = n2u2. For example, 2.8 m = 280 cm; 6.2 kg = 6200 g.

Table of Contents

- Units

- Dimensions

- What Is the Dimensional Formula?

- Limitations

- Physical Constants

- Dimensional Formulas for Physical Quantities

- Quantities with the Same Dimensional Formula

- Applications

- FAQs

Fundamental and Derived Quantities

- The quantities that are independent of other quantities are called fundamental quantities. The units that are used to measure these fundamental quantities are called fundamental units. There are four systems of units, namely CGS, MKS, FPS and SI.

- The quantities that are derived using the fundamental quantities are called derived quantities. The units that are used to measure these derived quantities are called derived units.

Fundamental and supplementary physical quantities in the SI system

| Fundamental

Quantity |

System of Units |

||

| CGS | MKS | FPS | |

| Length | centimeter | meter | foot |

| Mass | gram | kilogram | pound |

| Time | second | second | second |

| Physical Quantity | Unit | Symbol |

| Length | meter | m |

| Mass | kilogram | kg |

| Time | second | s |

| Electric current | ampere | A |

| Thermodynamic temperature | kelvin | K |

| Intensity of light | candela | cd |

| Quantity of substance | mole | mol |

Supplementary Quantities

| Plane angle | Radian | rad |

| Solid angle | Steradian | sr |

Most SI units are used in scientific research. SI is a coherent system of units.

A coherent system of units is one in which the units of derived quantities are obtained as multiples or submultiples of certain basic units. The SI system is a comprehensive, coherent and rationalised MKS. The ampere system (RMKSA system) was devised by Prof. Giorgi.

- Meter: A meter is equal to 1650763.73 times the wavelength of the light emitted in a vacuum due to the electronic transition from 2p10 state to 5d5 state in Krypton-86. But in 1983, the 17th General Assembly of Weights and Measures adopted a new definition for the meter in terms of the velocity of light. According to this definition, a meter is defined as the distance travelled by light in a vacuum during a time interval of 1/299, 792, 458 of a second.

- Kilogram: The mass of a cylinder of platinum-iridium alloy kept in the International Bureau of Weights and Measures preserved at Serves near Paris is called one kilogram.

- Second: The duration of 9192631770 periods of radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of cesium-133 atoms is called one second.

- Ampere: The current which, when flowing in each of two parallel conductors of infinite length and negligible cross-section and placed one meter apart in vacuum, causes each conductor to experience a force of 2 × 10-7 newtons per meter of length is known as one ampere.

- Kelvin: The fraction of 1/273.16 of the thermodynamic temperature of the triple point of water is called Kelvin.

- Candela: The luminous intensity in the perpendicular direction of a surface of a black body of area 1/600000 m2 at the temperature of solidifying platinum under a pressure of 101325 Nm-2 is known as one candela.

- Mole: The amount of a substance of a system which contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 12 × 10-3 kg of carbon-12 is known as one mole.

- Radian: The angle made by an arc of the circle equivalent to its radius at the centre is known as a radian. 1 radian = 57o17l45ll.

- Steradian: The angle subtended at the centre by one square meter area of the surface of a sphere of radius one meter is known as steradian.

Some Important Conclusions

- Angstrom is the unit of length used to measure the wavelength of light. 1 Å = 10-10 m.

- Fermi is the unit of length used to measure nuclear distances. 1 Fermi = 10-15 meter.

- A light year is the unit of length for measuring astronomical distances.

- Light year = distance travelled by light in 1 year = 9.4605 × 1015 m.

- Astronomical unit = Mean distance between the sun and earth = 1.5 × 1011 m.

- Parsec = 3.26 light years = 3.084×1016 m.

- Barn is the unit of area for measuring scattering cross-section of collisions. 1 barn = 10-28 m2.

- Chronometer and metronome are time-measuring instruments. The quantity having the same unit in all the systems of units is time.

⇒ Also Read: List of All SI Units

| MACRO Prefixes | MICRO Prefixes |

| Kilo (K) 103

Mega (M) 106 Giga (G) 109 Tera (T) 1012 Peta (P) 1015 Exa (E) 1018 Zetta (Z) 1021 Yotta (y) 1024 |

milli (m) 10-3

(μ) 10-6 nano (n) 10-9 pico (p) 10-12 femto (f)10-15 atto (a) 10-18 zepto (z) 10-21 yocto (y) 10-24 |

Note: The following are not used in the SI system.

- deca 101 deci 10-1

- hecta 102 centi 10-2

How to Write Units of Physical Quantities?

1. Full names of the units, even when they are named after a scientist, should not be written with a capital letter. For example, newton, watt, ampere, meter

2. The unit should be written either in full or in agreed symbols only

3. Units do not take the plural form. For example, 10 kg but not 10 kgs, 20 w but not 20 ws

4. No full stop or punctuation mark should be used within or at the end of symbols for units. For example, 10 W but not 10 W.

What Are Dimensions?

Dimensions of a physical quantity are the powers to which the fundamental units are raised to obtain one unit of that quantity.

Dimensional Analysis

Dimensional analysis is the practice of checking relations between physical quantities by identifying the dimensions of the physical quantities. These dimensions are independent of the numerical multiples and constants, and all the quantities in the world can be expressed as a function of the fundamental dimensions.

Read More: Dimensional Analysis

Dimensional Formula

The expression showing the powers to which the fundamental units are to be raised to obtain one unit of a derived quantity is called the dimensional formula of that quantity.

If Q is the unit of a derived quantity represented by Q = MaLbTc, then MaLbTc is called the dimensional formula, and the exponents a, b, and c are called dimensions.

What Are Dimensional Constants?

The physical quantities with dimensions and a fixed value are called dimensional constants. For example, gravitational constant (G), Planck’s constant (h), universal gas constant (R), velocity of light in a vacuum (C), etc.

What Are Dimensionless Quantities?

Dimensionless quantities are those which do not have dimensions but have a fixed value.

- Dimensionless quantities without units: Pure numbers, π, e, sin θ, cos θ, tan θ etc.

- Dimensionless quantities with units: Angular displacement – radian, Joule’s constant – joule/calorie, etc.

What Are Dimensional Variables?

Dimensional variables are those physical quantities which have dimensions and do not have a fixed value. For example, velocity, acceleration, force, work, power, etc.

What Are the Dimensionless Variables?

Dimensionless variables are those physical quantities which do not have dimensions and do not have a fixed value. For example, specific gravity, refractive index, the coefficient of friction, Poisson’s ratio, etc.

Law of Homogeneity of Dimensions

- In any correct equation representing the relation between physical quantities, the dimensions of all the terms must be the same on both sides. Terms separated by ‘+’ or ‘–’ must have the same dimensions.

- A physical quantity Q has dimensions a, b and c in length (L), mass (M) and time (T), respectively, and n1 is its numerical value in a system in which the fundamental units are L1, M1 and T1 and n2 is the numerical value in another system in which the fundamental units are L2, M2 and T2, respectively, then

Limitations of Dimensional Analysis

- Dimensionless quantities cannot be determined by this method. Also, the constant of proportionality cannot be determined by this method. They can be found either by experiment (or) by theory.

- This method does not apply to trigonometric, logarithmic and exponential functions.

- This method will be difficult in the case of physical quantities, which are dependent upon more than three physical quantities.

- In some cases, the constant of proportionality also possesses dimensions. In such cases, we cannot use this system.

- If one side of the equation contains the addition or subtraction of physical quantities, we cannot use this method to derive the expression.

Some Important Conversions

- 1 bar = 106 dyne/cm2 = 105 Nm-2 = 105 pascal

- 76 cm of Hg = 1.013×106 dyne/cm2 = 1.013×105 pascal = 1.013 bar.

- 1 toricelli or torr = 1 mm of Hg = 1.333×103 dyne/cm2 = 1.333 millibar.

- 1 kmph = 5/18 ms-1

- 1 dyne = 10-5 N,

- 1 H.P = 746 watt

- 1 kilowatt hour = 36×105 J

- 1 kgwt = g newton

- 1 calorie = 4.2 joule

- 1 electron volt = 1.602×10-19 joule

- 1 erg = 10-7 joule

Some Important Physical Constants

- Velocity of light in vacuum (c) = 3 × 108 ms-1

- Velocity of sound in air at STP = 331 ms-1

- Acceleration due to gravity (g) = 9.81 ms-2

- Avogadro number (N) = 6.023 × 1023/mol

- Density of water at 4oC = 1000 kgm-3 or 1 g/cc.

- Absolute zero = -273.15oC or 0 K

- Atomic mass unit = 1.66 × 10-27 kg

- Quantum of charge (e) = 1.602 × 10-19 C

- Stefan’s constant = 5.67 × 10–8 W/m2/K4

- Boltzmann’s constant (K) = 1.381 × 10-23 JK-1

- One atmosphere = 76 cm Hg = 1.013 × 105 Pa

- Mechanical equivalent of heat (J) = 4.186 J/cal

- Planck’s constant (h) = 6.626 × 10-34 Js

- Universal gas constant (R) = 8.314 J/mol–K

- Permeability of free space (μ0) = 4π × 10-7 Hm-1

- Permittivity of free space (ε0) = 8.854 × 10-12 Fm-1

- The density of air at S.T.P. = 1.293 kg m-3

- Universal gravitational constant = 6.67 × 10-11 Nm2kg-2

Derived SI units with Special Names

| Physical Quantity | SI Unit | Symbol |

| Frequency | hertz | Hz |

| Energy | joule | J |

| Force | newton | N |

| Power | watt | W |

| Pressure | pascal | Pa |

| Electric charge or

quantity of electricity |

coulomb | C |

| Electric potential difference and emf | volt | V |

| Electric resistance | ohm | \(\begin{array}{l}\Omega\end{array} \) |

| Electric conductance | siemen | S |

| Electric capacitance | farad | F |

| Magnetic flux | weber | Wb |

| Inductance | henry | H |

| Magnetic flux density | tesla | T |

| Illumination | lux | Lx |

| Luminous flux | lumen | Lm |

Dimensional Formulas for Physical Quantities

| Physical Quantity | Unit | Dimensional Formula |

| Acceleration or acceleration due to gravity | ms–2 | LT–2 |

| Angle (arc/radius) | rad | MoLoTo |

| Angular displacement | rad | MoloTo |

| Angular frequency (angular displacement/time) | rads–1 | T–1 |

| Angular impulse (torque x time) | Nms | ML2T–1 |

| Angular momentum (Iω) | kgm2s–1 | ML2T–1 |

| Angular velocity (angle/time) | rads–1 | T–1 |

| Area (length x breadth) | m2 | L2 |

| Boltzmann’s constant | JK–1 | ML2T–2θ–1 |

| Bulk modulus \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\Delta P.\frac{V}{\Delta V} \right)\end{array} \) |

Nm–2, Pa | M1L–1T–2 |

| Calorific value | Jkg–1 | L2T–2 |

| Coefficient of linear or areal or volume expansion | oC–1 or K–1 | θ–1 |

| Coefficient of surface tension (force/length) | Nm–1 or Jm–2 | MT–2 |

| Coefficient of thermal conductivity | Wm–1K–1 | MLT–3θ–1 |

| Coefficient of viscosity \(\begin{array}{l}\left(F=\eta A\frac{dv}{dx} \right)\end{array} \) |

poise | ML–1T–1 |

| Compressibility (1/bulk modulus) | Pa–1, m2N–2 | M–1LT2 |

| Density (mass/volume) | kgm–3 | ML–3 |

| Displacement, wavelength, focal length | m | L |

| Electric capacitance (charge/potential) | CV–1, farad | M–1L–2T4I2 |

| Electric conductance (1/resistance) | Ohm–1 or mho or siemen | M–1L–2T3I2 |

| Electric conductivity (1/resistivity) | siemen/metre or Sm–1 | M–1L–3T3I2 |

| Electric charge or quantity of electric charge (current x time) | coulomb | IT |

| Electric current | ampere | I |

| Electric dipole moment (charge x distance) | Cm | LTI |

| Electric field strength or intensity of electric field (force/charge) | NC–1, Vm–1 | MLT–3I–1 |

| Electric resistance \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\frac{potential\ difference}{current} \right)\end{array} \) |

ohm | ML2T–3I–2 |

| Emf (or) electric potential (work/charge) | volt | ML2T–3I–1 |

| Energy (capacity to do work) | joule | ML2T–2 |

| Energy density \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\frac{energy}{volume} \right)\end{array} \) |

Jm–3 | ML–1T–2 |

| Entropy \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\Delta S=\Delta Q/T \right)\end{array} \) |

Jθ–1 | ML2T–2θ–1 |

| Force (mass x acceleration) | newton (N) | MLT–2 |

| Force constant or spring constant (force/extension) | Nm–1 | MT–2 |

| Frequency (1/period) | Hz | T–1 |

| Gravitational potential (work/mass) | Jkg–1 | L2T–2 |

| Heat (energy) | J or calorie | ML2T–2 |

| Illumination (Illuminance) | lux (lumen/metre2) | MT–3 |

| Impulse (force x time) | Ns or kgms–1 | MLT–1 |

| Inductance (L) \(\begin{array}{l}\left(energy =\frac{1}{2}L{{I}^{2}} \right)\end{array} \) or

coefficient of self-induction |

henry (H) | ML2T–2I–2 |

| Intensity of gravitational field (F/m) | Nkg–1 | L1T–2 |

| Intensity of magnetization (I) | Am–1 | L–1I |

| Joule’s constant or mechanical equivalent of heat | Jcal–1 | MoLoTo |

| Latent heat (Q = mL) | Jkg–1 | MoL2T–2 |

| Linear density (mass per unit length) | kgm–1 | ML–1 |

| Luminous flux | lumen or (Js–1) | ML2T–3 |

| Magnetic dipole moment | Am2 | L2I |

| Magnetic flux (magnetic induction x area) | weber (Wb) | ML2T–2I–1 |

| Magnetic induction (F = Bil) | NI–1m–1 or T | MT–2I–1 |

| Magnetic pole strength (unit: ampere–meter) | Am | LI |

| Modulus of elasticity (stress/strain) | Nm–2, Pa | ML–1T–2 |

| Moment of inertia (mass x radius2) | kgm2 | ML2 |

| Momentum (mass x velocity) | kgms–1 | MLT–1 |

| Permeability of free space \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\mu_o = \frac{4\pi Fd^{2}}{m_1m_2} \right)\end{array} \) |

Hm–1 or NA–2 | MLT–2I–2 |

| Permittivity of free space \(\begin{array}{l}\left({{\varepsilon }_{o}}=\frac{{{Q}_{1}}{{Q}_{2}}}{4\pi F{{d}^{2}}} \right)\end{array} \) |

Fm–1 or C2N–1m–2 | M–1L–3T4I2 |

| Planck’s constant (energy/frequency) | Js | ML2T–1 |

| Poisson’s ratio (lateral strain/longitudinal strain) | –– | MoLoTo |

| Power (work/time) | Js–1 or watt (W) | ML2T–3 |

| Pressure (force/area) | Nm–2 or Pa | ML–1T–2 |

| Pressure coefficient or volume coefficient | oC–1 or θ–1 | θ–1 |

| Pressure head | m | MoLTo |

| Radioactivity | disintegrations per second | MoLoT–1 |

| Ratio of specific heats | –– | MoLoTo |

| Refractive index | –– | MoLoTo |

| Resistivity or specific resistance | \(\begin{array}{l}\Omega\end{array} \) –m |

ML3T–3I–2 |

| Specific conductance or conductivity (1/specific resistance) | siemen/metre or Sm–1 | M–1L–3T3I2 |

| Specific entropy (1/entropy) | KJ–1 | M–1L–2T2θ |

| Specific gravity (density of the substance/density of water) | –– | MoLoTo |

| Specific heat (Q = mst) | Jkg–1θ–1 | MoL2T–2θ–1 |

| Specific volume (1/density) | m3kg–1 | M–1L3 |

| Speed (distance/time) | ms–1 | LT–1 |

| Stefan’s constant \(\begin{array}{l}\left( \frac{heat\ energy}{area\ x\ time\ x\ temperatur{{e}^{4}}} \right)\end{array} \) . |

Wm–2θ–4 | MLoT–3θ–4 |

| Strain (change in dimension/original dimension) | –– | MoLoTo |

| Stress (restoring force/area) | Nm–2 or Pa | ML–1T–2 |

| Surface energy density (energy/area) | Jm–2 | MT–2 |

| Temperature | oC or θ | MoLoToθ |

| Temperature gradient \(\begin{array}{l}\left(\frac{change\text{ in temperature}}{\text{distance}} \right)\end{array} \) |

oCm–1 or θm–1 | MoL–1Toθ |

| Thermal capacity (mass x specific heat) | Jθ–1 | ML2T–2θ–1 |

| Time period | second | T |

| Torque or moment of force (force x distance) | Nm | ML2T–2 |

| Universal gas constant (work/temperature) | Jmol–1θ–1 | ML2T–2θ–1 |

| Universal gravitational constant \(\begin{array}{l}\left(F = G.\frac{{{m}_{1}}{{m}_{2}}}{{{d}^{2}}} \right)\end{array} \) |

Nm2kg–2 | M–1L3T–2 |

| Velocity (displacement/time) | ms–1 | LT–1 |

| Velocity gradient (dv/dx) | s–1 | T–1 |

| Volume (length x breadth x height) | m3 | L3 |

| Water equivalent | kg | MLoTo |

| Work (force x displacement) | J | ML2T–2 |

Quantities Having the Same Dimensional Formula

- Impulse and momentum.

- Work, torque, the moment of force, energy.

- Angular momentum, Planck’s constant, rotational impulse.

- Stress, pressure, modulus of elasticity, energy density.

- Force constant, surface tension, surface energy.

- Angular velocity, frequency, velocity gradient.

- Gravitational potential, latent heat.

- Thermal capacity, entropy, universal gas constant and Boltzmann’s constant.

- Force, thrust.

- Power, luminous flux.

Applications of Dimensional Analysis

Dimensional analysis is very important when dealing with physical quantities. In this section, we will learn about some applications of dimensional analysis.

Fourier laid down the foundations of dimensional analysis. The dimensional formulas are used to:

- Verify the correctness of a physical equation.

- Derive a relationship between physical quantities.

- Converting the units of a physical quantity from one system to another system.

Checking the Dimensional Consistency

As we know, only similar physical quantities can be added or subtracted. Thus, two quantities having different dimensions cannot be added together. For example, we cannot add mass and force or electric potential and resistance.

For any given equation, the principle of homogeneity of dimensions is used to check the correctness and consistency of the equation. The dimensions of each component on either side of the sign of equality are checked, and if they are not the same, the equation is considered wrong.

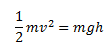

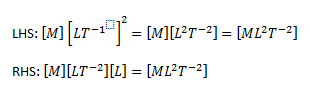

Let us consider the equation given below,

The dimensions of the LHS and the RHS are calculated

As we can see, the dimensions of the LHS and the RHS are the same. Hence, the equation is consistent.

Deducing the Relation among Physical Quantities

Dimensional analysis is also used to deduce the relation between two or more physical quantities. If we know the degree of dependence of a physical quantity on another, that is, the degree to which one quantity changes with the change in another, we can use the principle of consistency of two expressions to find the equation relating to these two quantities. This can be understood more easily through the following illustration.

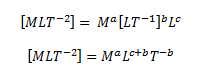

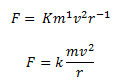

Example: Derive the formula for centripetal force F acting on a particle moving in a uniform circle.

As we know, the centripetal force acting on a particle moving in a uniform circle depends on its mass m, velocity v and the radius r of the circle. Hence, we can write

F = ma vb rc

Writing the dimensions of these quantities,

As per the principle of homogeneity, we can write,

a = 1, b + c = 1 and b = 2

Solving the above three equations, we get, a = 1, b = 2 and c = -1.

Hence, the centripetal force F can be represented as,

Recommended Videos

Units & Dimensions – Vernier Calliper’s

Units & Dimensions – Screw Gauge

Units & Dimensions – Important Questions

Units & Dimensions – Introduction Concepts

Units & Dimensions – SI System and Parallax

Frequently Asked Questions on Units and Dimensions

What is the meaning of dimension in Physics?

It is an expression that relates derived quantities to fundamental quantities. But it is not related to the magnitude of the derived quantity.

What is the dimension of force?

We know that, F = ma —– (1)

Mass is a fundamental quantity, but acceleration is a derived quantity and can be represented in terms of fundamental quantities.

a = [LT−2] —– (2)

Using (1) and (2),

F = [MLT−2]

This is the dimension of force.

What is dimensional analysis?

Dimensional analysis is based on the principle that two quantities can be compared only if they have the same dimensions. For example, I can compare kinetic energy with potential energy and say they are equal, or one is greater than another because they have the same dimension. But I cannot compare kinetic energy with force or acceleration as their dimensions are different.

How do you demonstrate dimensional analysis with an example?

Suppose I have the following equation,

F = Ea.Vb. Tc

Where, F = Force; E = Energy; V = Velocity; M = Mass

We need to find the value of a, b and c.

Following are the dimensions of the given quantities,

F = [MLT−2], E = [ML2T−2], V = [LT−1]

According to dimensional analysis, the dimension of RHS should be equal to LHS; hence,

[MLT−2] = [ML2T−2]a . [LT−1]b. [T]c

[MLT−2] = [Ma L2a+b T−2a−b+c]

Now, we have three equations,

a = 1

2a+b = 1

−2a − b + c = −2

Solving the three equations, we get,

a = 1, b = −1 and c = −1.

What is meant by a unit?

The standard quantity with which a physical quantity of the same kind is compared is called a unit.

Why are mass, length, and time chosen as fundamental or base quantities in mechanics?

This is because mass, length and time are independent of each other. All the other quantities in mechanics can be expressed in terms of mass, length and time.

Define significant figures.

Significant figures are those digits in a number known with certainty plus one more uncertain number.

Define dimensions.

The dimensions of a physical quantity are the powers to which the fundamental quantities are raised to represent that physical quantity.

Clear cut explanation. All my confusions are cleared.

This piece of information is very helpful.

Thank you