What Is Conduction?

Conduction, in general, is the process of transmission of energy from one particle of the medium to the other, but here, each particle of the medium stays at its own position. In Physics and Chemistry, the meaning of conduction is understood mainly as the transfer of heat energy or an electric charge through a material. Conduction can occur in solids, liquids, and gases.

When conduction of heat occurs, the heat energy is usually transferred from one molecule to another molecule as they are in direct contact with each other. However, there is no change in the position of the molecules. They simply vibrate amongst each other.

During the conduction of electricity, there is a movement of electrically charged particles in the medium. As such, the electric current is usually carried and moved by the ions or electrons.

Read in Detail:

Conduction Examples

A simple example of conduction that we can take is, if you hold an iron rod with one of its ends over a fire for some time, the handle gets hot. What is happening here is that the heat is being transferred from the tip that is kept in the fire to the handle by conduction along the length of the iron rod. The vibrational amplitude of atoms and electrons in the iron rod at the hot end takes on relatively higher values due to the higher temperature of their environment.

These increased vibrational amplitudes are transferred along the rod, from atom to atom, during the collision between adjacent atoms. In this way, a region of rising temperature extends itself along the rod to your hand.

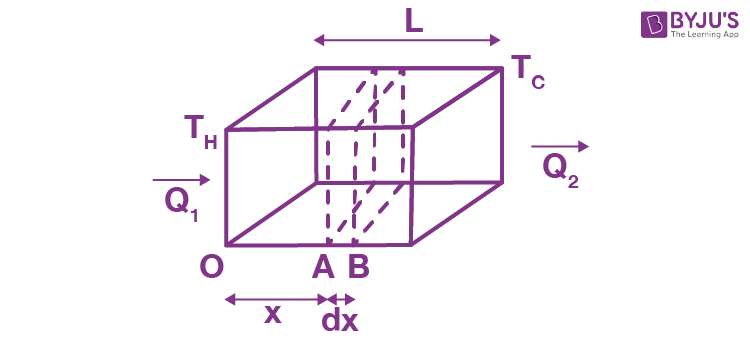

Consider a slab of face area A, lateral thickness L, whose faces have temperatures TH and TC(TH > TC).

Now, consider two cross-sections in the slab at positions A and B, separated by a lateral distance of dx. Let the temperature of face A be T and that of face B be T + DT. Then, the experiment shows that Q, the amount of heat crossing the area A of the slab at position x in time t, is given by

Here, K is a constant depending on the material of the slab and is named the thermal conductivity of the material, and the quantity (dT/dx) is called a temperature gradient. The (_) sign in Equation (1) shows heat flows from high to low temperatures.

Types of Conduction

There are two main types of conduction. They are as follows:

- Steady-state conduction

- Transient conduction

Steady-State Conduction

If the temperature of a cross-section at any position x in the above slab remains constant with time (remember, it does vary with position x), the slab is said to be in steady-state.

Remember, steady-state is distinct from thermal equilibrium, for which temperature at any position (x) in the slab must be the same.

For a conductor in steady-state, there is no absorption or emission of heat at any cross-section (as the temperature at each point remains constant with time). The left and right faces are maintained at constant temperatures, TH and TC, respectively, and all other faces must be covered with adiabatic walls so that no heat escapes through them and the same amount of heat flows through each cross-section in a given interval of time. Hence, Q1 = Q = Q2. Consequently, the temperature gradient is constant throughout the slab.

Hence,

and

Here, Q is the amount of heat flowing through a cross-section of the slab at any position in a time interval of t.

Example 1: One face of an aluminium cube of edge 2 meters is maintained at 100ºC, and the other end is maintained at 0ºC. All other surfaces are covered by adiabatic walls. Find the amount of heat flowing through the cube in 5 seconds. (thermal conductivity of aluminium is 209 W/mºC).

Sol. The heat will flow from the end at 100ºC to the end at 0ºC.

Area of a cross-section perpendicular to the direction of heat flow is,

A = 4m2

Then,

Transient Conduction or Non-Steady-State Conduction

During transient conduction, the temperatures can change or vary at any part within an object at a given time. This mode of conduction is also termed “non-steady-state” conduction. Basically, the main point that we have to consider here is the object’s time dependence on temperature.

Non-steady-state conduction usually occurs when a change in temperature is introduced within the outer areas of an object or inside. The temperature change is brought about by the sudden entry of a new source of heat within the object.

An example of transient conduction is the starting of an engine in a vehicle. In this case, a new source of heat is added when the engine is turned on. However, the transient thermal conduction phase is only for a brief moment of time. As the engine reaches a certain operating temperature, the steady-state phase appears.

Fourier’s Law

Fourier’s law is also known as the law of heat conduction. The law states, “The rate of heat transfer through a material is proportional to the negative gradient in the temperature and to the area, at right angles to that gradient, through which the heat flows.”

The law can further be expressed in two forms – the integral and differential forms. In the integral form, we consider the amount of energy that is moving in or out of a body in total. In the differential form, we consider the rate of flow or the energy fluxes locally.

Meanwhile, Fourier’s law also has various representations, such as Newton’s law of cooling which is its discrete analogue and Ohm’s law which is its electrical analogue.

Thermal Resistance to Conduction

If you are interested in insulating your house from cold weather or, for that matter keeping the meal hot in your tiffin box, you are more interested in poor heat conductors rather than good conductors. For this reason, the concept of thermal resistance R has been introduced.

For a slab of cross-section A, lateral thickness L and thermal conductivity K,

In terms of R, the amount of heat flowing through a slab in steady-state (in time t)

If we name Q/t as thermal current iT, then

This is mathematically equivalent to Ohm’s law, with temperature doing the role of electric potential. Hence, results derived from Ohm’s law are also valid for thermal conduction.

Moreover, for a slab in steady-state, we have seen earlier that the thermal current iL remains the same at each cross-section. This is analogous to Kirchoff’s current law in electricity, which can now be very conveniently applied to thermal conduction.

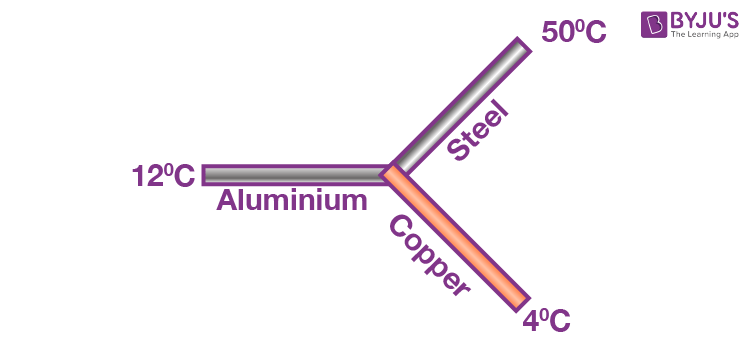

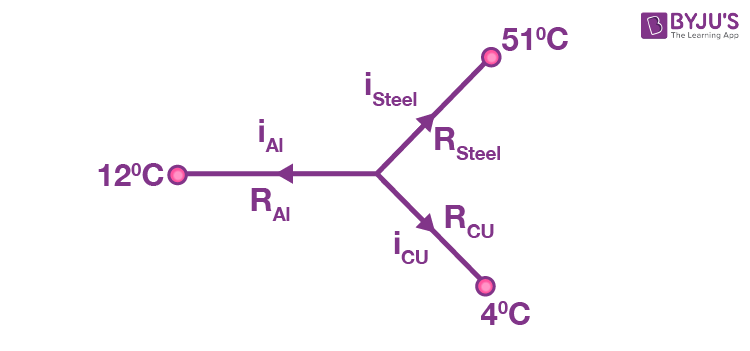

Example 2: Three identical rods of length 1 m each, having cross-section area of 1 cm2 each and made of aluminium, copper and steel, respectively, are maintained at temperatures of 12ºC, 4ºC and 50ºC respectively, at their separate ends.

Find the temperature of their common junction.

[ KCu = 400 W/m-K , KAl = 200 W/m-K , Ksteel = 50 W/m-K ]Sol:

Similarly,

Let the temperature of the common junction = T

Then, from Kirchhoff’s current laws,

iAl + isteel + iCu = 0

(T _ 12) 200 + (T _ 50) 50 + (T _ 4) 400

4(T _ 12) + (T _ 50) + 8 (T _ 4) = 0

13T = 48 + 50 + 32 = 130

Þ T = 10ºC

Heat Conduction through Slab

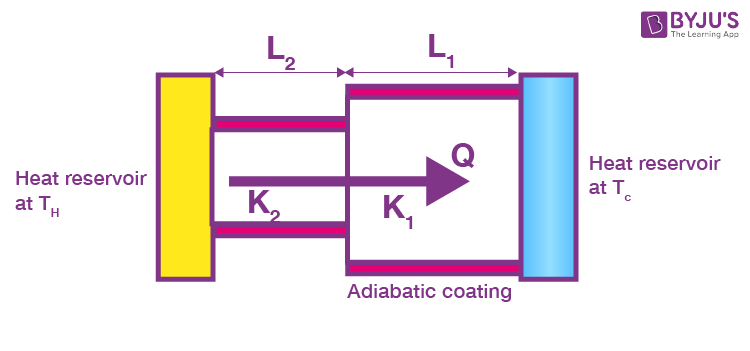

Slabs in Series (in Steady-state)

Consider a composite slab consisting of two materials having different thicknesses L1 and L2, different cross-sectional areas A1 and A2 and different thermal conductivities K1 and K2. The temperature at the outer surface of the states is maintained at TH and TC, and all lateral surfaces are covered by an adiabatic coating.

Let temperature at the junction be T, since steady-state has been achieved thermal current through each slab and will be equal. Then, the thermal current is through the first slab.

And that through the second slab,

Adding Equations 1 and 2,

TH _ TC = (R1 + R2) i

or

Thus, these two slabs are equivalent to a single slab of thermal resistance R1 + R2.

If more than two slabs are joined in series and are allowed to attain steady-state, then equivalent thermal resistance is given by

R = R1 + R2 + R3 + ……. …

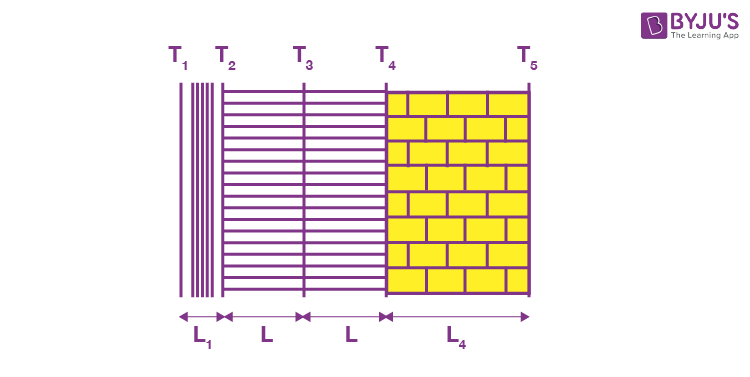

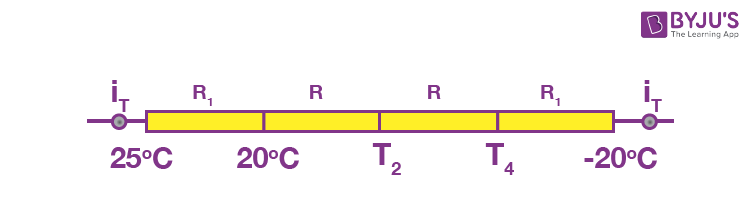

Example 3: The figure shows the cross-section of the outer wall of a house built in a hill resort to keep the house insulated from the freezing temperature outside. The wall consists of teak wood of thickness L1 and brick of thickness (L2 = 5L1), sandwiching two layers of an unknown material with identical thermal conductivities and thickness. The thermal conductivity of teak wood is K1, and that of brick is (K2 = 5K). Heat conduction through the wall has reached a steady-state, with the temperature of three surfaces being known. (T1 = 25ºC, T2 = 20ºC and T5 = – 20ºC). Find the interface temperature T4 and T3.

Sol. Let the interface area be A., then the thermal resistance of the wood,

And that of the brick wall,

Let the thermal resistance of each sand witch layer = R. Then, the above wall can be visualised as a circuit.

The thermal current through each wall is the same.

Hence,

25 _ 20 = T4 + 20

T4 = _15ºC

also, 20 _ T3 = T3 _ T4

Example 4: In example 3, K1 = 0.125 W/m_ºC, K2 = 5K1 = 0.625 W/m_ºC and thermal conductivity of the unknown material is K = 0.25 W/mºC. L1 = 4cm, L2 = 5L1 = 20 cm and L = 10 cm. If the house consists of a single room with a total wall area of 100 m2, then find the power of the electric heater being used in the room.

Sol.

Heat transfer rate i = (TH – TC)/Ri

TH = 250 C

TC = 200C

R1 = L1/K1A

= 4 x 10-2/(0.125 x 100) = 4 x 10-2/125 = 32 x 10-4 0C/W

Therefore, i = (25 – 20)/ (32 x 10-4 )

= 5/32 x 10-4

= 1562.5 Watt

= 1.56 KWatt.

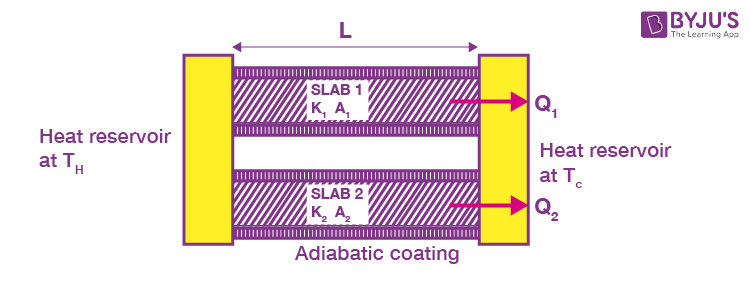

Slabs in Parallel

Consider two slabs held between the same heat reservoirs, their thermal conductivities K1 and K2 and cross-sectional areas A1 and A2

Then,

And that through Slab 2

Net heat current from the hot to cold reservoir

If more than two rods are joined in parallel, the equivalent thermal resistance is given by

Also Read: Semiconductors

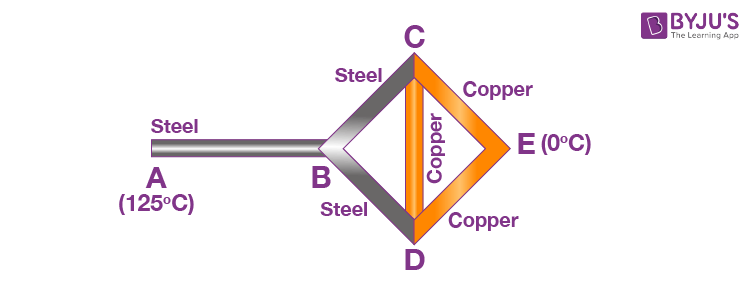

Example 5: Three copper rods and three steel rods each of length l = 10 cm and area of cross-section 1 cm2 are connected as shown in the figure.

If ends A and E are maintained at temperatures 125ºC and 0ºC respectively, calculate the amount of heat flowing per second from the hot to cold function. [ KCu = 400 W/m-K , Ksteel = 50 W/m-K ]

Sol.

Similarly,

Junctions C and D are identical in every respect, and both will have the same temperature. Consequently, the rod CD is in thermal equilibrium, and no heat will flow through it. Hence, it can be neglected in further analysis.

Now, rod BC and CE are in series, and their equivalent resistance is R1 = RS + RCu. Similarly, rods BD and DE are in series with the same equivalent resistance R1 = RS + RCu.

These two are in parallel, giving an equivalent resistance of

This resistance is connected in series with rod AB. Hence, the net equivalent of the combination is

Now

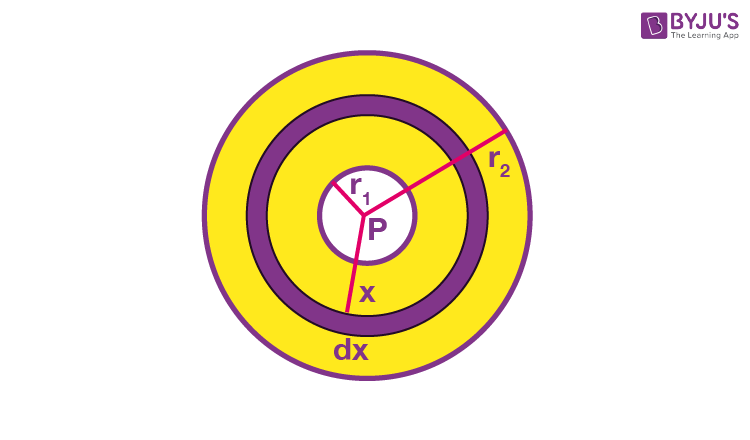

Example 6: Two thin concentric shells made from copper with radius r1 and r2 (r2 > r1) have material of thermal conductivity K filled between them. The inner and outer spheres are maintained at temperatures TH and TC, respectively, by keeping a heater of power P at the centre of the two spheres. Find the value of P.

Sol. Heat flowing per second through each cross-section of the sphere = P = i.

The thermal resistance of the spherical shell of radius x and thickness dx,

Thermal current,

Example 7: A container of negligible heat capacity contains 1 kg of water. It is connected by a steel rod of length 10 m and area of cross-section 10 cm2 to a large steam chamber, which is maintained at 100ºC. If the initial temperature of the water is 0ºC, find the time after which it becomes 50ºC. (Neglect heat capacity of steel rod and assume no loss of heat to surroundings), (Use table 3.1; take specific heat of water = 4180 J/kg ºC).

Sol. Let the temperature of water at time t be T, then the thermal current at time t,

This increases the temperature of water from T to T + dT

or t = Rms in 2 seconds

= 6.27 × 105 sec

= 174.16 hours.

Can you now see how the following facts can be explained by thermal conduction?

(a) In winter, iron chairs appear to be colder than wooden chairs.

(b) Ice is covered in gunny bags to prevent melting.

(c) Woollen clothes are warmer.

(d) We feel warmer in a fur coat.

(e) Two thin blankets are warmer than a single blanket of double the thickness.

(f) Birds often swell their feathers in winter.

(g) A new quilt is warmer than the old one.

(h) Kettles are provided with wooden handles.

(i) Eskimos make double-walled ice houses.

(j) A thermos flask is made double-walled.

What Is Convection?

When heat is transferred from one point to the other through the actual movement of heated particles, the process of heat transfer is called convection. In liquids and gases, some heat may be transported through conduction. But most of the transfer of heat in them occurs through the process of convection. Convection is caused by the earth’s gravity. Normally, the portion of fluid at a greater temperature is less dense, while that at a lower temperature is denser. Hence, hot fluids rise up, and white colder fluid sink down, accounting for convection. In the absence of gravity, convection would not be possible.

Also, the anomalous behaviour of water (its density increases with temperature in the range of 0-4ºC) give rise to interesting consequences vis-a-vis the process of convection. One of these interesting consequences is the presence of aquatic life in temperate and polar waters. The other is the rain cycle.

Can you now see how the following facts can be explained by thermal convection?

(a) Oceans freeze top-down and not bottom-up. (This fact is singularly responsible for the presence of aquatic life in temperate and polar waters.)

(b) The temperature at the bottom of deep oceans is invariably 4ºC, whether it is winter or summer.

(c) You cannot illuminate the interior of a lift in free fall or an artificial satellite of earth with a candle.

(d) You can illuminate your room with a candle.

You might also be interested in the following:

Frequently Asked Questions on Conduction

Give an example of conduction in everyday life.

Heating of a pan placed on a stove.

What are the three types of conduction?

Heat conduction

Electric conduction

Photoconductivity

What is convection?

Convection is the process of heat transfer by the movement of the heated fluid, such as water or air.

What are the modes of heat transfer?

Conduction

Convection

Radiation

Comments